Constructive Chaos.

Making things make sense.

Making things make sense.

Terranaut

MFA Thesis | Parsons School of Design | 2023Terranaut is a sustainable mud playground that explores the interplay between creation and discovery.

Co-created with children aged 4-10 from Artshack Brooklyn Ceramics, Terranaut reimagines the future of playscapes by using intuitive forms and natural materials, prioritizing the mental and physical well-being of those who engage with it.

Terranaut surfaces the tension of earthen structures in an urban environment by juxtaposing unexpected natural forms with the industrial, rectilinear structures of New York City’s architecture.

Co-created with children aged 4-10 from Artshack Brooklyn Ceramics, Terranaut reimagines the future of playscapes by using intuitive forms and natural materials, prioritizing the mental and physical well-being of those who engage with it.

Terranaut surfaces the tension of earthen structures in an urban environment by juxtaposing unexpected natural forms with the industrial, rectilinear structures of New York City’s architecture.

Background | Reasearch + Development | Process | Proposal

A (very) brief history of earthen architecture

We are inextricably connected to mud.

Humanity would not have evolved in the way that we have without it – it has shaped everything from our built environment to our biology. It isn’t just a material, but a matter interlaced with practice, culture, science, and spirit. Earthen architecture has been a part of human history for 11,000 years. It was only recently that society pulled away from these traditions with the Industrial Revolution.

A (very) brief introduction to mud + human health

Humus, the organic matter in soil, influences human health mentally and physically. It stimulates the release of oxytocin, the “love hormone,” associated with trust, bonding, and emotional well-being, while the microbiome of soil has the capacity to help regulate our immune system.

Exposure to soil, particularly during early childhood, has been shown to reduce the risk of asthma, allergies, and autoimmune disorders later in life. Microorganisms in soil help balance the body's stress response by influencing cortisol levels, thus preventing chronic inflammation which can lead to cardiovascular disease, gastrointenstinal diseases, cancer, neaurological disorders, diabetes, depression, and anxiety.

Humanity would not have evolved in the way that we have without it – it has shaped everything from our built environment to our biology. It isn’t just a material, but a matter interlaced with practice, culture, science, and spirit. Earthen architecture has been a part of human history for 11,000 years. It was only recently that society pulled away from these traditions with the Industrial Revolution.

A (very) brief introduction to mud + human health

Humus, the organic matter in soil, influences human health mentally and physically. It stimulates the release of oxytocin, the “love hormone,” associated with trust, bonding, and emotional well-being, while the microbiome of soil has the capacity to help regulate our immune system.

Exposure to soil, particularly during early childhood, has been shown to reduce the risk of asthma, allergies, and autoimmune disorders later in life. Microorganisms in soil help balance the body's stress response by influencing cortisol levels, thus preventing chronic inflammation which can lead to cardiovascular disease, gastrointenstinal diseases, cancer, neaurological disorders, diabetes, depression, and anxiety.

1. Material Engagement Theory as Design Methodology

Terranaut was driven by “Material Engagement Theory” (MET), a term coined by the cognitive archeologist Lambros Malafouris, which proposes that the interactions between people and the material world shape human cognition and culture.

Materials/objects are not just a passive reflection of human thought and behavior but active participants in shaping it. MET views the mind as embodied, extended, and distributed rather than “all in our head” – it challenges the idea that we either discover or create and suggests instead that we discover by creating.

The concept of “discovering by creating” felt particularly interesting in the context of design methodology, where traditionally, an idea is conceptualized, iterated, developed, then delivered.

I wondered what it would be like to explore form without preconceiving an outcome by letting the material (mud) drive development.

Terranaut was driven by “Material Engagement Theory” (MET), a term coined by the cognitive archeologist Lambros Malafouris, which proposes that the interactions between people and the material world shape human cognition and culture.

Materials/objects are not just a passive reflection of human thought and behavior but active participants in shaping it. MET views the mind as embodied, extended, and distributed rather than “all in our head” – it challenges the idea that we either discover or create and suggests instead that we discover by creating.

The concept of “discovering by creating” felt particularly interesting in the context of design methodology, where traditionally, an idea is conceptualized, iterated, developed, then delivered.

I wondered what it would be like to explore form without preconceiving an outcome by letting the material (mud) drive development.

2. Mud Making Sessions at Parsons

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

I brought my members of my cohort together at Parsons to play with mud in “mud making sessions.”

After these sessions, I was left with several undefined mud objects and didn’t know what to do with them, so I borrowed a method I use in my art practice: 3D scanning rocks and/or handbuilt clay pieces, then digitally sculpting them in Rhinoceros 3D to prepare for fabrication.

When I repeated this process with the mud objects, I noticed something: the objects maintained their intrinsic character, distinctly connected to the earth, resembling landscapes.

At that point, I thought: “What an interesting terrain! I would love to climb it,” and that’s when the idea of a playground emerged.

I brought my members of my cohort together at Parsons to play with mud in “mud making sessions.”

After these sessions, I was left with several undefined mud objects and didn’t know what to do with them, so I borrowed a method I use in my art practice: 3D scanning rocks and/or handbuilt clay pieces, then digitally sculpting them in Rhinoceros 3D to prepare for fabrication.

When I repeated this process with the mud objects, I noticed something: the objects maintained their intrinsic character, distinctly connected to the earth, resembling landscapes.

At that point, I thought: “What an interesting terrain! I would love to climb it,” and that’s when the idea of a playground emerged.

3. 3D Scans

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4. Noguchi

Isamu Noguchi was a Japanese-American artist and landscape architect known for his work in sculpture, furniture, lighting, and playground design.

I first learned of his playgrounds when a friend pointed out similarities between his designs and the 3D scans above.

Noguchi saw playgrounds as spaces for children to explore shapes and functions in a simple, evocative way, promoting learning through play. His philosophy, known as "non-directive play," encourages children to interpret and define their play without being limited by specific equipment like slides or swings.

For the two years I was in graduate school, I worked part-time as a ceramics teacher at a local studio, working primarly with elementary aged kids. Once the idea of a playground emerged, I decided to turn to them (with permission from their parents) as co-creators. After all, what better expert on playground design than a child?

Isamu Noguchi was a Japanese-American artist and landscape architect known for his work in sculpture, furniture, lighting, and playground design.

I first learned of his playgrounds when a friend pointed out similarities between his designs and the 3D scans above.

Noguchi saw playgrounds as spaces for children to explore shapes and functions in a simple, evocative way, promoting learning through play. His philosophy, known as "non-directive play," encourages children to interpret and define their play without being limited by specific equipment like slides or swings.

For the two years I was in graduate school, I worked part-time as a ceramics teacher at a local studio, working primarly with elementary aged kids. Once the idea of a playground emerged, I decided to turn to them (with permission from their parents) as co-creators. After all, what better expert on playground design than a child?

5. World Building at Artshack

Instead of leading with “I want to build an abstract earthen playground to promote non-directive play and creativity,” I started with a game of hide-and seek, which served as a world-building exercise.

My students and I discussed the relationship between their bodies and space by asking: “what are the best places to hide and why?” “Is it more fun to hide with friends or alone?” “Is it better to hide in plain sight or crawl into/under something to be completely concealed?” Etc. Then, we brainstormed what the "perfect world to play hide and seek" might look like.

From there, I gave them each a ball of clay – we used clay instead of mud because it’s still “of the earth,” but it’s a material they’re familiar with.

They built clay sculptures of their worlds, some collaborating, others working independently. The youngest of the group made abstract forms, while the older kids, upon realizing we were designing a playground, started creating more recognizable elements like balance beams and swings.

Instead of leading with “I want to build an abstract earthen playground to promote non-directive play and creativity,” I started with a game of hide-and seek, which served as a world-building exercise.

My students and I discussed the relationship between their bodies and space by asking: “what are the best places to hide and why?” “Is it more fun to hide with friends or alone?” “Is it better to hide in plain sight or crawl into/under something to be completely concealed?” Etc. Then, we brainstormed what the "perfect world to play hide and seek" might look like.

From there, I gave them each a ball of clay – we used clay instead of mud because it’s still “of the earth,” but it’s a material they’re familiar with.

They built clay sculptures of their worlds, some collaborating, others working independently. The youngest of the group made abstract forms, while the older kids, upon realizing we were designing a playground, started creating more recognizable elements like balance beams and swings.

6. “The Perfect World for Hide and Seek”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

We iterated on their worlds over the course of a month

results

7. Artshack Forms

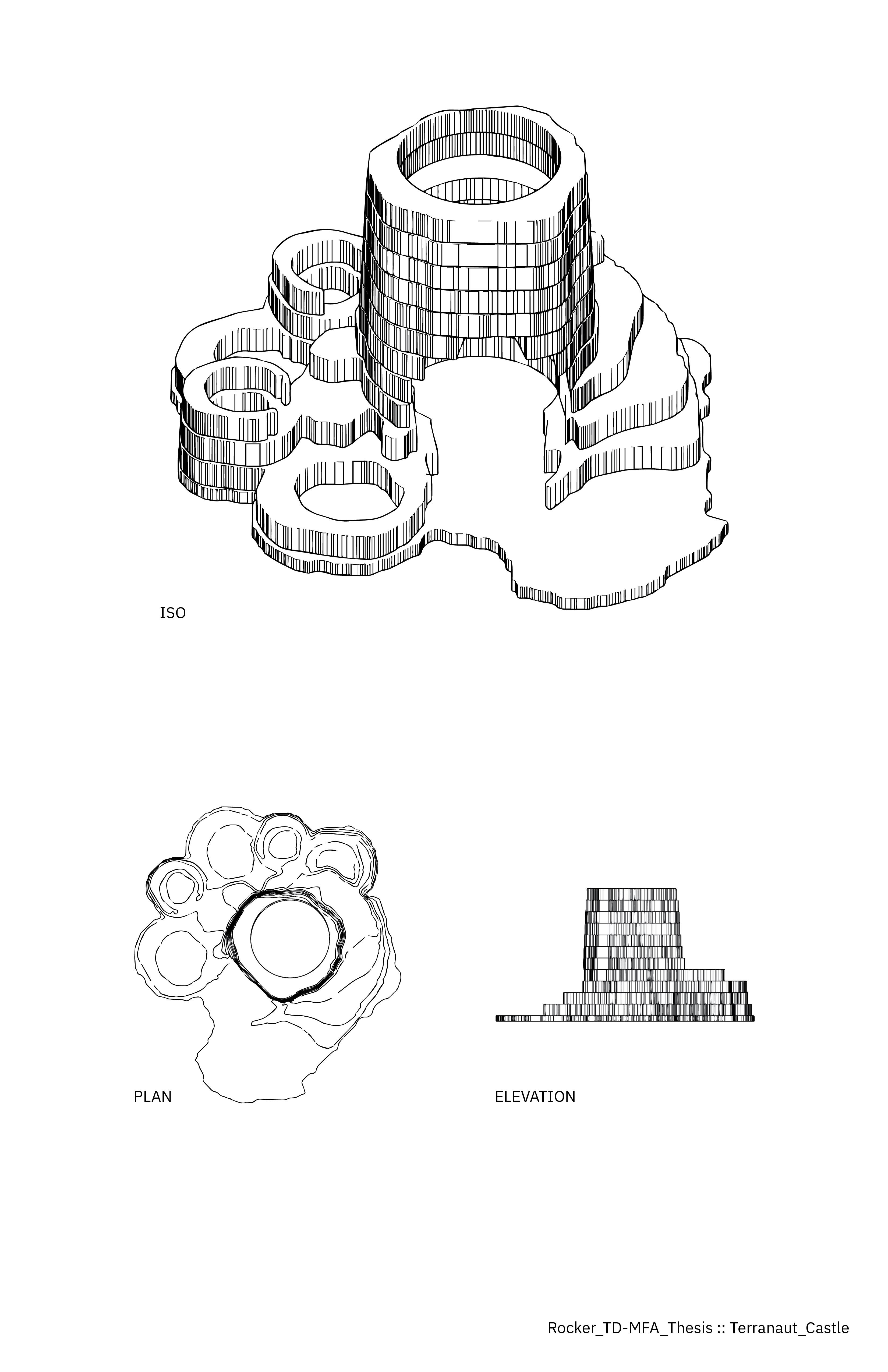

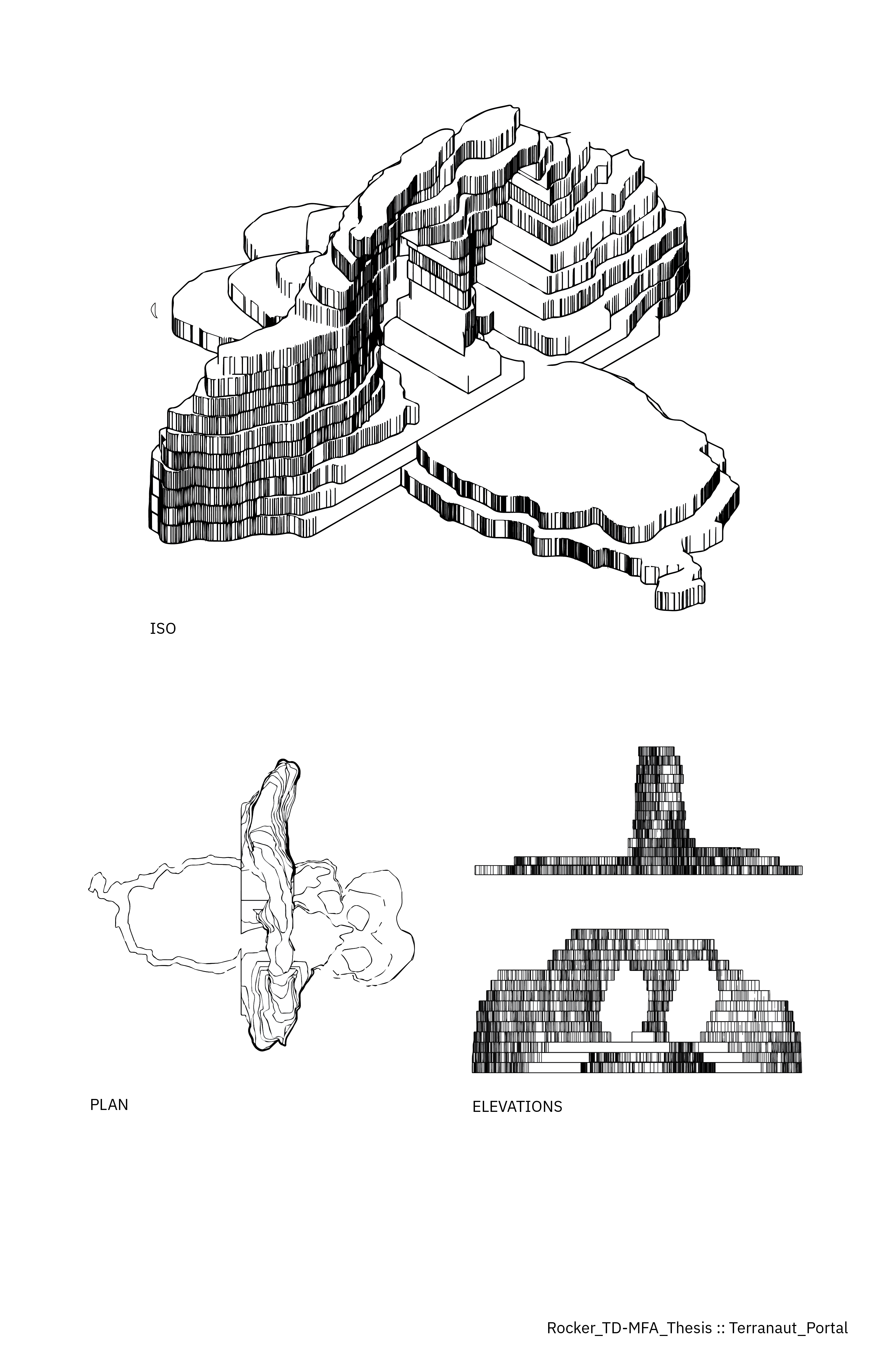

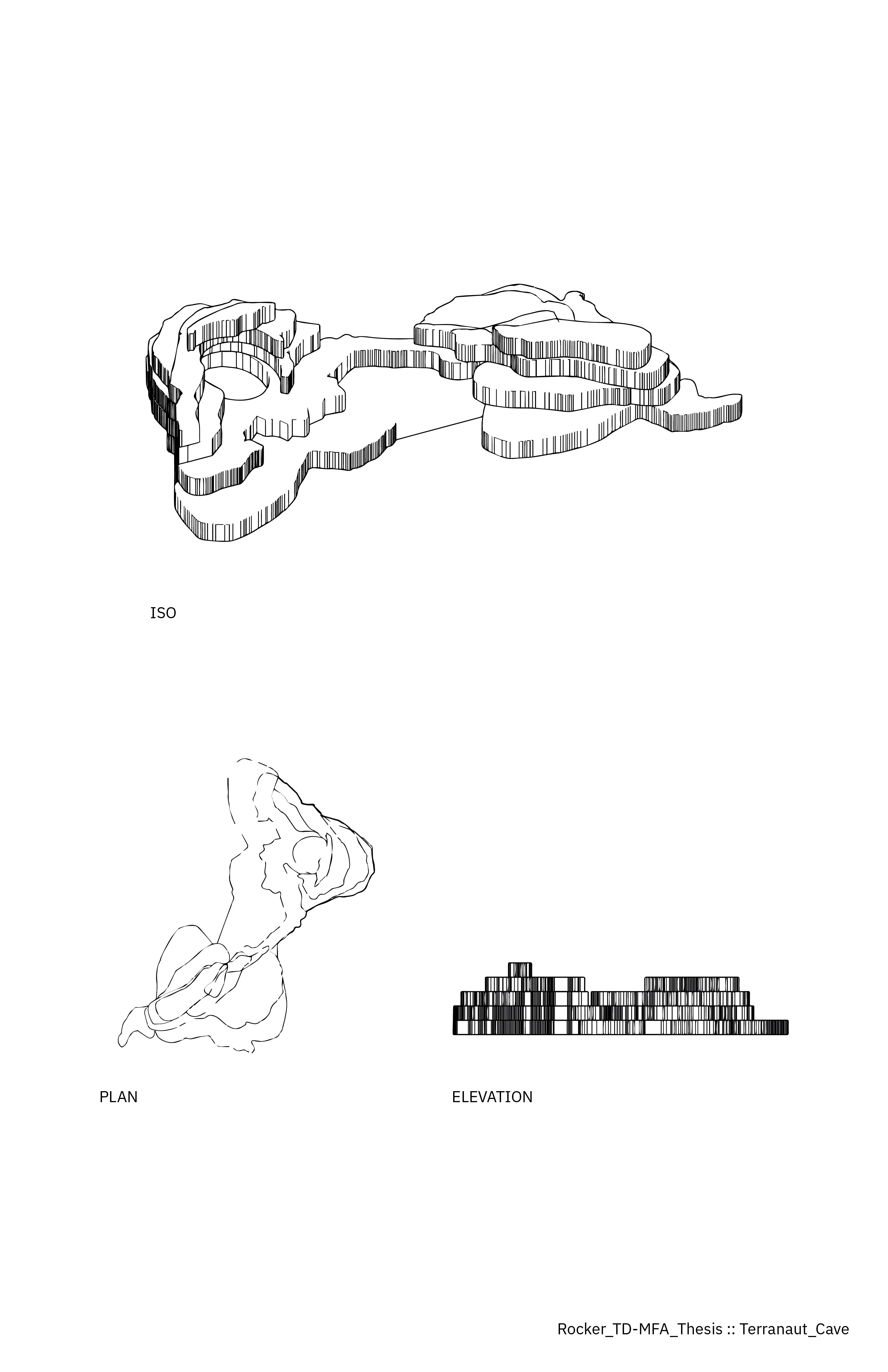

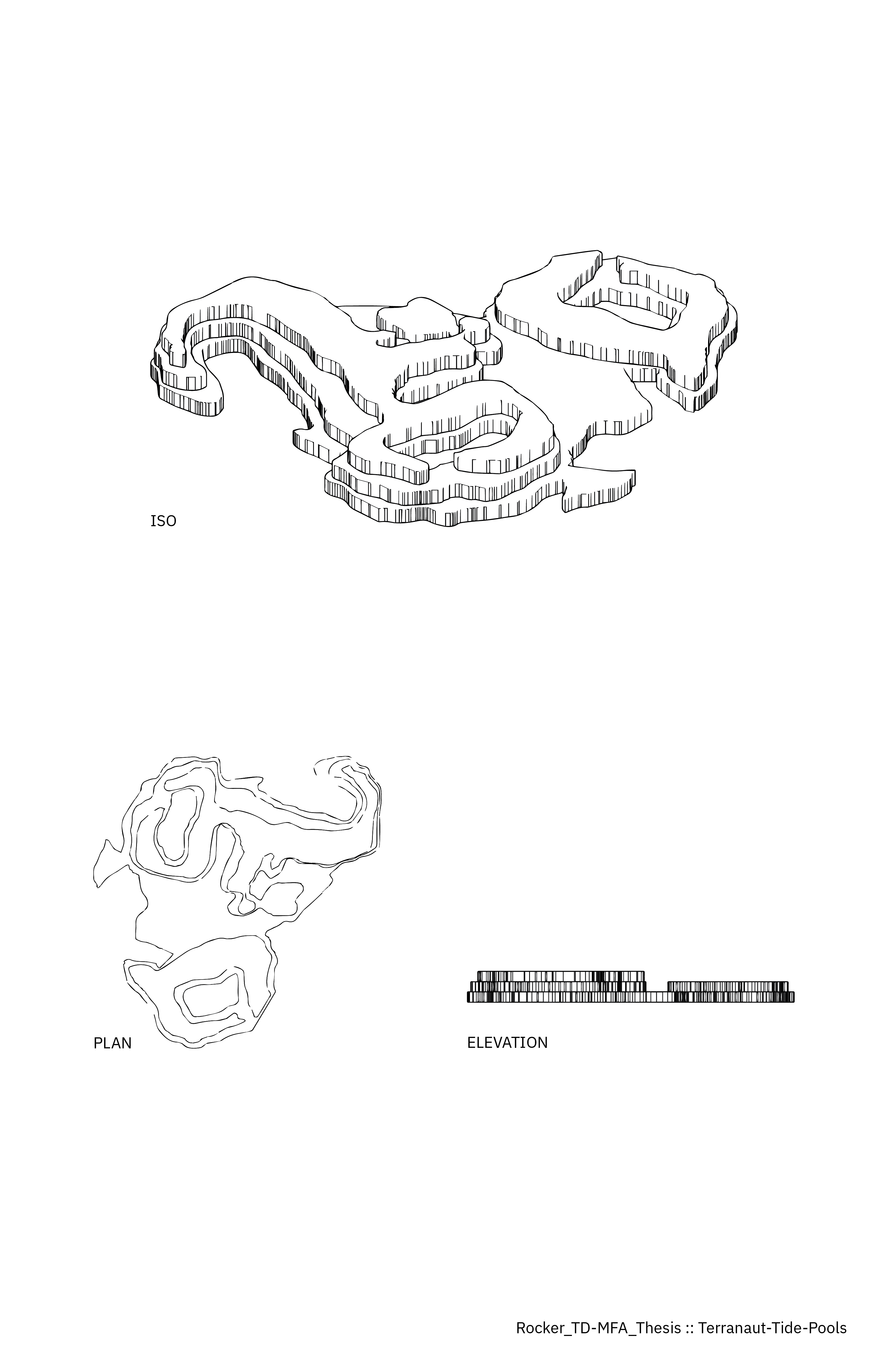

After the kids finished their sculptures, I 3D scanned the pieces to create an archive in Rhinoceros 3D.

Their pieces were more complex than other forms I had worked with, so I imposed some constraints on myself.

Instead of rationalizing all of their sculptures, I combined the designs to create five new, but still recognizable, forms. I used our conversations and the elements they liked most to drive the design forward. Then I rationalized those five structures to be fabricated at playground scale, using standard safety regulations for playgrounds to determine size.

After the kids finished their sculptures, I 3D scanned the pieces to create an archive in Rhinoceros 3D.

Their pieces were more complex than other forms I had worked with, so I imposed some constraints on myself.

Instead of rationalizing all of their sculptures, I combined the designs to create five new, but still recognizable, forms. I used our conversations and the elements they liked most to drive the design forward. Then I rationalized those five structures to be fabricated at playground scale, using standard safety regulations for playgrounds to determine size.

8. Proposed Site: Herbert Von King, Brooklyn NY.

Herbert Von King is one of Brooklyn’s oldest parks, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, the same landscape architects who created Central Park.

It has barbeque pits, a baseball diamond, an amphitheater, and a dog run, making it a vibrant community space. Most of the park’s programming is done through The Herbert Von King Cultural Arts Center, which showcases temporary sculptural installations done by local artists.

But most importantly, Herbert Von King is in the neighborhood. Artshack is located the Bedford Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, the same neighborhood where many of my students live, go to school, and play. It didn’t feel right to propose this project anywhere other than the neighborhood in which it was created.

![]()

![]()

Herbert Von King is one of Brooklyn’s oldest parks, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, the same landscape architects who created Central Park.

It has barbeque pits, a baseball diamond, an amphitheater, and a dog run, making it a vibrant community space. Most of the park’s programming is done through The Herbert Von King Cultural Arts Center, which showcases temporary sculptural installations done by local artists.

But most importantly, Herbert Von King is in the neighborhood. Artshack is located the Bedford Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, the same neighborhood where many of my students live, go to school, and play. It didn’t feel right to propose this project anywhere other than the neighborhood in which it was created.

9. Proposed Soil Source: NYC Clean Soil Bank

New York City's surface soil is often contaminated, but deeper soil is typically healthier.

The New York City Clean Soil Bank recovers clean soil from deep excavations at construction sites and redirects it to other projects like community and school gardens and stormwater protection at minimal cost.

The organization connects soil-generating sites with soil-receiving sites, making it easy for both to participate. Soil is free for receiving sites, though they may pay for transportation. An earthen playground in NYC would likely last 1-3 years due to the city's climate, after which the soil could be reused for a new playground, converted into a garden, or repurposed for other projects, creating a closed-loop system.

New York City's surface soil is often contaminated, but deeper soil is typically healthier.

The New York City Clean Soil Bank recovers clean soil from deep excavations at construction sites and redirects it to other projects like community and school gardens and stormwater protection at minimal cost.

The organization connects soil-generating sites with soil-receiving sites, making it easy for both to participate. Soil is free for receiving sites, though they may pay for transportation. An earthen playground in NYC would likely last 1-3 years due to the city's climate, after which the soil could be reused for a new playground, converted into a garden, or repurposed for other projects, creating a closed-loop system.

10. Proposed Fabrication Method

The emerging technology of earthen 3D printing with a SCARA Robot or a variation of SuperAdobe, without barbed wire.

![]()

![]()

examples of earthen 3D printing taken during the summer I spent assisting Sandy Curth in his dissertation work with MIT.

The emerging technology of earthen 3D printing with a SCARA Robot or a variation of SuperAdobe, without barbed wire.

examples of earthen 3D printing taken during the summer I spent assisting Sandy Curth in his dissertation work with MIT.

Terranaut:

Terranaut is an interactive earthen playground proposal for the Cultural Arts Center at Herbert Von King Park in Brooklyn. Named as a nod to Noguchi, who wished for people to feel like the first person to explore Earth. Terranaut will be created using soil sourced from the NYC Clean Soil Bank and built through earthen 3D printing or a variation of super adobe techniques. Temporary in nature, it will last one to three years, evolving with weather and children's play patterns. The structures will be sustainable, with the soil being reused for future playgrounds, gardens, or returned to the Clean Soil Bank.

The project addresses the tension between New York City’s urban landscape and the organic, intuitive nature of earthen materials. By integrating mud into the city’s environment, Terranaut offers a unique opportunity to reconnect people with the earth and provide exposure to its microbiome, which benefits immune health and allergy prevention, especially for children. Beyond its physical impact, the project introduces alternative building methods to urban communities and inspires future applications of earthen construction in temporary or public structures.

Terranaut also serves as a platform for education, where children, teens, and young adults can learn valuable skills—from ceramics (in ideating the structures) and CAD design (taking the 3D scans and and making them buildable) to marketing and proposal writing (to bring future playgrounds to life)—while co-creating the space.

By bringing communities together to build the final structure, Terranaut fosters a sense of ownership and connection. Terranaut represents a small, meaningful shift toward sustainability, community, and a deeper connection with the earth, making the world a little better tomorrow than it is today.

Terranaut is an interactive earthen playground proposal for the Cultural Arts Center at Herbert Von King Park in Brooklyn. Named as a nod to Noguchi, who wished for people to feel like the first person to explore Earth. Terranaut will be created using soil sourced from the NYC Clean Soil Bank and built through earthen 3D printing or a variation of super adobe techniques. Temporary in nature, it will last one to three years, evolving with weather and children's play patterns. The structures will be sustainable, with the soil being reused for future playgrounds, gardens, or returned to the Clean Soil Bank.

The project addresses the tension between New York City’s urban landscape and the organic, intuitive nature of earthen materials. By integrating mud into the city’s environment, Terranaut offers a unique opportunity to reconnect people with the earth and provide exposure to its microbiome, which benefits immune health and allergy prevention, especially for children. Beyond its physical impact, the project introduces alternative building methods to urban communities and inspires future applications of earthen construction in temporary or public structures.

Terranaut also serves as a platform for education, where children, teens, and young adults can learn valuable skills—from ceramics (in ideating the structures) and CAD design (taking the 3D scans and and making them buildable) to marketing and proposal writing (to bring future playgrounds to life)—while co-creating the space.

By bringing communities together to build the final structure, Terranaut fosters a sense of ownership and connection. Terranaut represents a small, meaningful shift toward sustainability, community, and a deeper connection with the earth, making the world a little better tomorrow than it is today.